QMP Racing’s Brad Lagman tells us how.

There’s information about your performance and machining processes hiding in your surface texture. But you need to be able to see it to improve it.

No one knows this better than Brad Lagman, founder of QMP Racing Engines in Chatsworth, California. Lagman has been building engines for drag racing, street car racing, NHRA/IHRA, drag boats, and anything that goes very fast, since 1987.

Engineering, art, and raw power meet in a product of QMP Racing. Courtesy QMP Racing and Krookid Photography

QMP has a well-earned reputation for building and machining winning engines. At the heart of this success is QMP’s dedication to the latest in engine manufacturing technology—and Brad’s passion for always pushing to be better. “I want to be the best in what I do. There is always room for improvements. That’s my motivation.”

“It also fuels my massive ego,” he jokes.

We sat down with Brad, the larger-than-life personality who fuels QMP, to talk about how he and QMP mine surface texture for every ounce of performance from their engines.

Brad Lagman and one of his creations. Courtesy Dragzine.

Measuring and tracking surface roughness

Measuring and interpreting surface roughness data is part of QMP’s DNA. Lagman explains that they track the data throughout the life of an engine—through the manufacturing process of course, but also updating records each time an engine is run-in, raced, and returned with the customers’ evaluations. That information loop is key. “We can only get better by feedback,” says Lagman.

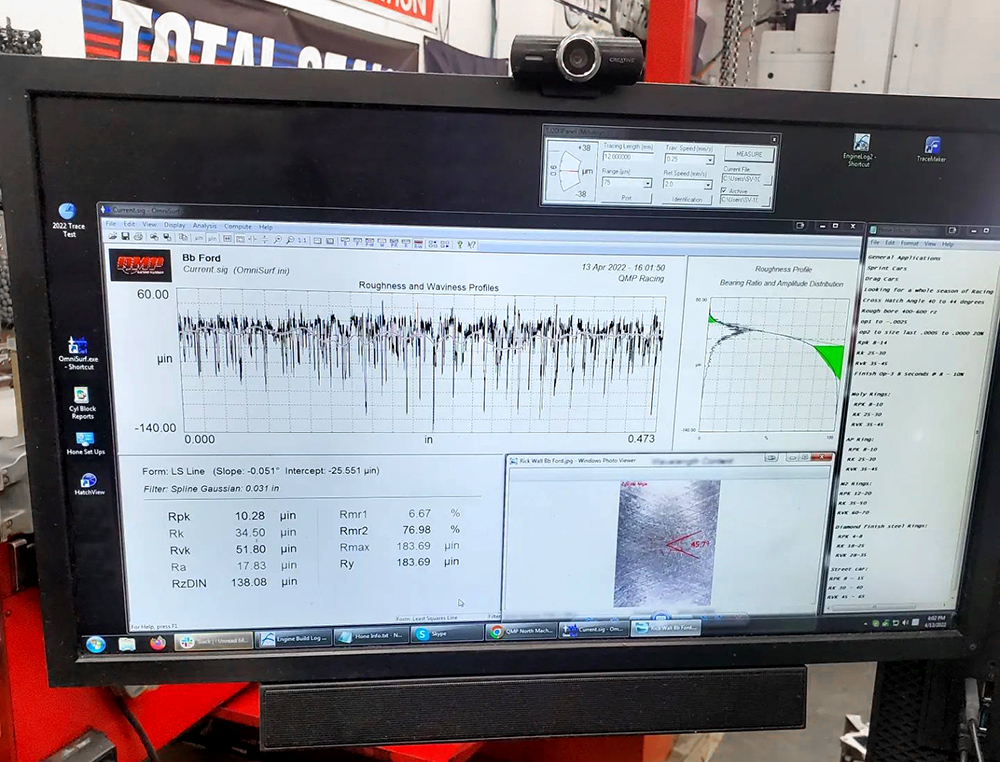

While meeting an Ra (average roughness) specification is sufficient to verify some surfaces in the shop, Lagman says, “An Ra finish is irrelevant in a cylinder wall,” because the highly engineered surface must be optimized for a range of functions (learn more in our Specification and Measurement of Plateau Honed Surfaces tutorial). Lagman says he primarily tracks Rz (average peak-to-valley roughness) to control coarse honing, which creates the oil-retaining valleys in the texture. He then uses the bearing ratio parameters (Rk, Rpk, Rvk, etc.) to control fine honing, in order to dial in the ratios of peak material, core material, and valley material.

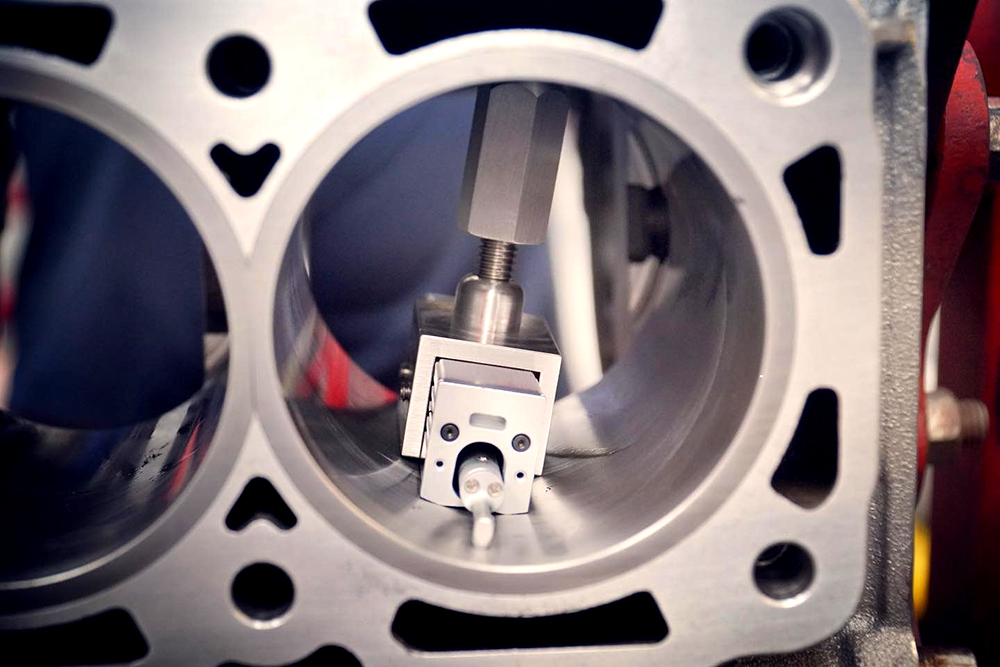

Measuring the surface roughness of a cylinder bore. Digital Metrology software and QMP’s surface texture probe/drive holder make the process efficient and fast. Courtesy QMP Racing.

Lagman uses cylinder bore finish as a lever for improving performance. The optimal texture differs for every application—and Lagman combines intuition with hard data to produce winning results across the board. For endurance racing, an engine needs to break in slowly, which calls for a hone that preserves core material over time. A top fuel engine, however, will only operate for a few seconds, with almost no break-in period, so the final hone needs to be much smoother. Block material, fuel, and lubricant all influence the honing process as well. To meet this wide range of very specific surface needs, QMP regularly keeps over one thousand types of honing stones on hand, meticulously organized and labeled.

One of the many drawers of honing stones at QMP Racing – each providing very specific texture controls. Courtesy QMP Racing.

Lagman and QMP have been dedicated to staying up to date with technologies to measure and analyze surface texture. The technology lets them close the loop between design assumptions, manufacturing data, and the hard truths of actual racing.

Seeing texture is key to understanding it

For Lagman, a key part of the process is Digital Metrology’s OmniSurf and HatchView software. Lagman has been using these two programs to guide his honing processes since he discovered them online around 2007. His OmniSurf system is set up to initiate stylus measurements directly from the computer. “Instead of reading numbers off the remote, the data feeds right to the software,” where he can immediately view the surface profile with critical parameters for the application. “It’s leaps and bounds better to see the data I need on one screen. I pick the parameters that I want, in the order I want to see them. They’re big, and I’m not squinting.” And seeing the profile, as opposed to viewing a number on a gage, makes the peaks and valleys visceral.

A surface roughness profile and parameters in OmniSurf. Courtesy QMP racing.

Tracking texture is key to improving it

QMP puts a lot of effort into measurement efficiency so that they can acquire more measurements per block and build a better picture of the texture. “We check all eight cylinders, four spots each, so we know that it’s not coming back. We can’t make money if it comes back.” The efficiency comes in part from the software, but also from other improvements such as custom probe holder—one of several innovations that QMP has developed and now sells.

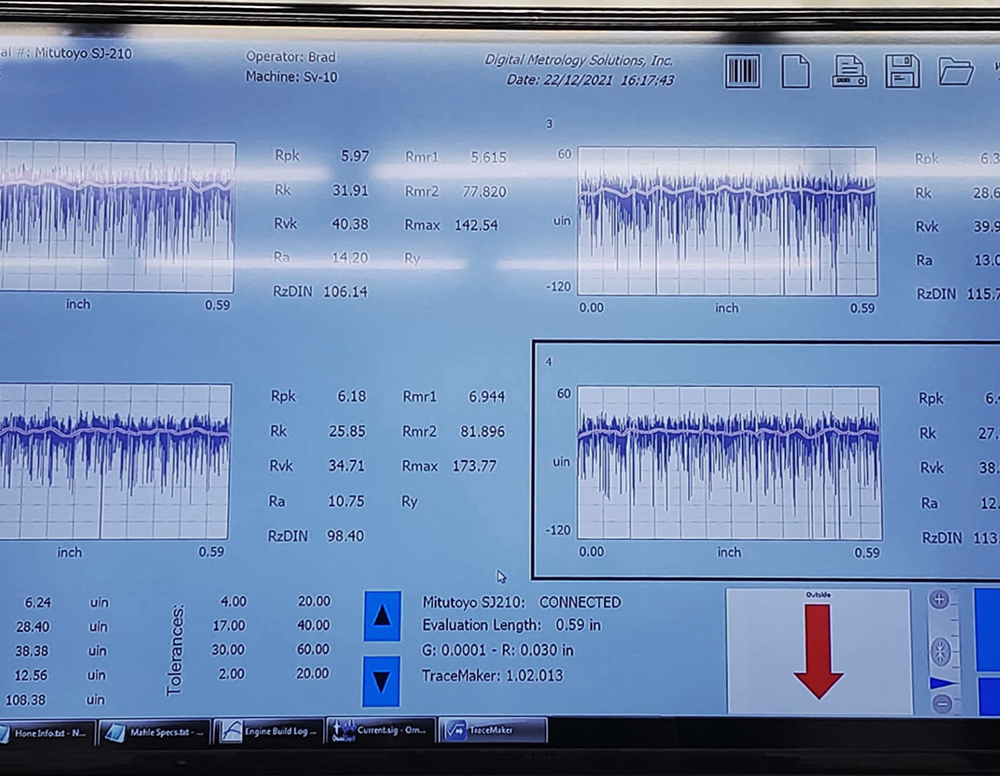

That level of quality control results in a huge amount of data. Lagman estimates that they maintain over one million profile measurements in their Performance Trends tracking system, which lets them reassess and update the data whenever the engine returns to the shop.

![]()

OmniSurf data is fed into the Performance Trends data management program. Courtesy QMP Racing.

The advantage? Engine performance improvement.

The key advantage of tracking all this data, says Lagman, is that it allows the company to constantly improve. “With OmniSurf and HatchView, you know the starting point, and you can tie it to the comeback info,” he explains. Each time an engine returns to the shop is an opportunity to log data, make adjustments, and learn a little more. “When you store the data, you can go back and look at it, and replicate it or make a change.”

Lagman says the benefits were almost immediate with OmniSurf, noting that he was able to begin using the software after “only a ten-minute conversation.” He has worked regularly with Digital Metrology’s Mark Malburg over the years to fine tune the software to his workflow and improve his efficiency.

What’s next?

Lagman says the industry is undergoing rapid change: thinner rings, harder blocks, new materials and coatings, changes to lubrication and fuel—on and on. To keep up, more manufacturers are now embracing surface texture measurement and investing in the technology to measure and track it.

Digital Metrology’s TraceMaker software on the big screen at QMP. Courtesy QMP Racing.

Technology, of course, can carry a price tag. While companies with deep pockets dominate some racing circuits, most racers and racing manufacturers must strike a balance between doing what it takes to win and doing what they can afford. For Lagman, products such as OmniSurf strike the right balance: providing essential data that shops and teams can afford. It has given him the ability to see what’s in his data, rather than just tracking “the number on the screen.”

That ability, coupled with Lagman’s enthusiasm, intuition, and commitment to improvement, has earned him an outsized reputation for winning.